At its south end, Lake Chelan doesn’t say “wild swim” the way other lakes do. At Don Morse Lakeshore Park, it says “recreational lake for summer tourists, locals, and Coppertone.” Which was fine. I’m all for people getting outside enjoying and recreating in nature. This was my first trip to Lake Chelan (pronounced by most as Shuh-lan) and I wanted to experience both this popular municipal beach near the (over)-developed south end of the lake and the remote shores of the north end 55 miles away near the remote village of Stehekin.

While a swim from the municipal beach was easy (almost a drive-up swim), getting to the remote north of the lake required more planning. Stehekin, like every place along the north half of the lake is accessible only by boat, floatplane, horseback, or by hiking trail.

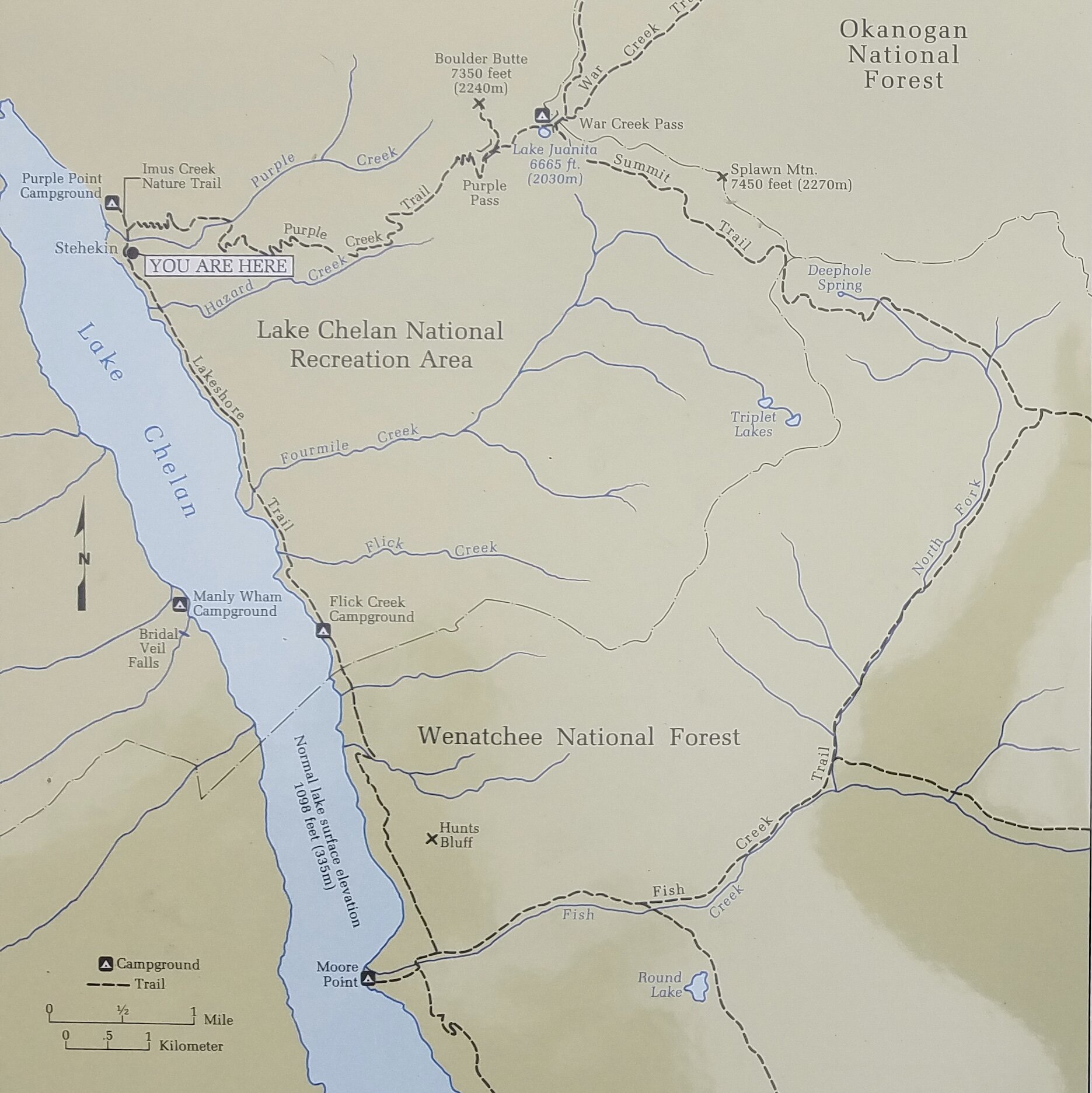

In the wake of the Pleistocene…a ice-gouged valley and a 1,485-foot-deep lake. (Photo by M. M. Ruth of map on display aboard the Lady of the Lake passenger ferry.

Lake Chelan is 55 miles long, between 1 and 2 miles wide (except at the narrows where it’s just 1/3 mile wide), and snakes its way across three separate Green Trails topographic map sheets (Nos. 82, 11, and 114). This lake is an unfathomable 1,485 feet deep at its deepest . It is the largest naturally-formed lake in Washington, though it cannot be called a natural lake due to the small dam built in 1928 at the south end. Lake Chelan developed in a broad glacial valley during the Pleistocene, about 2.5 million years ago. Everything north of the town of Chelan was buried under the Okanagan lobe of the ice sheet that covered the northern third of Washington. Lake Chelan is steep sided and surrounded by rugged wilderness areas, national forests, national recreation areas, and North Cascades National Park.

Most tourists do not come to Lake Chelan to swim, though there is a “family fun” open-water 1.5-mile Lake Chelan Swim event every Saturday after Labor Day from Manson Bay, eight miles north of the town of Chelan. They come to recreate around Chelan and to take the Lady of the Lake passenger ferry up the lake. Some passengers are bound for Holden Village, a former gold- and copper-mining town and now religious retreat operated by the Lutheran Church. Others deboard at “flag stops” (i.e. flag the captain and he’ll stop/crash the boat along the shore, extend the ramp/gang plank, and send you and your backpack on your merry way into the wilderness).

The Lady of the Lake passenger ferry runs daily trips from Chelan to Stehekin. It’s a grand way to enjoy the scenery, mingle with fellow travelers and residents, and enjoy the ferry captains’ informative narrative. Plan on making unscheduled stops for interesting sights and to drop off and pick up passengers hiking and camping in the wilderness areas surrounding the lake.

The majority of passengers are headed to Stehekin to spend just a few hours exploring the town, the valley, and famous Stehekin Bakery by shuttle bus. Others set off from Stehekin to hike the trails (including the Pacific Crest Trail) in the surrounding wilderness. Overnighters can camp along the lake or stay at the lovely historic North Cascades Lodge. Some will rent kayaks or canoes to explore the lake.

Kayaks rented from the North Cascades Lodge in Stehekin make a great way to explore Lake Chelan but be aware of shifting winds that can make paddling northward a slog. Photo by M.M. Ruth

Stand-Up Paddle Canoeing isn’t the rage yet on Lake Chelan but I recommend it for a pleasant change in perpective of the water and the clouds floating in it. Plus it gives the stearnsman a ridiculous photo op. (Photo by M.D. Ruth)

During the two days I stayed at the lodge, I did see two other swimmers (“bathers” might be a better term) but I think I was the only person who swam for pleasure.

“Pleasure” might be a bit of an overstatement. The water at the north end of Lake Chelan at Stehekin was much colder than at the south end. A short hike south on the Lakeshore Trail lead us to Flick Creek campground and a decent-enough access point. And by “us” I mean me. My three companions were not interested in sharing my obsession with wild swimming on this day.

This was one of the briskest swims I took all summer. I’d say it was below 60 degrees—but the clouds and the wind made it seem colder. I guess if meteorologists can talk about “wind-chill factor,” I can talk about “cloud-chop” factor. I swam in 52-degree water in March, but the water was calm and the day was an unseasonably warm and sunny 80 degrees. There is some interesting research on our perception of “cold” water. The air temperature, wind, cloud cover, our mood, our caffeine level, our previous night’s alcohol consumption, and other factors influence not only our perception of the water temperature but also our ability to tolerate it.

Advice: If you are a) solo swimming in a 1,486-foot-deep lake and are b) not wearing a wet suit and c) not accompanied by anyone interested in or willing to get in the water and d) the water is really really cold and choppy and e) it is cloudy and cool…do not stay in long or go far from shore. This swim in Lake Chelan qualified for a-e and so was under ten minutes. (Photo by M.D. Ruth)

And shortly before getting on the ferry to return home, I took a swim near the boat docks in front of the North Cascades Lodge. A very easy access point and I had enough time to swim to this mooring log and back. I’m so glad I did so I can keep living up to my motto: Never give up an opportunity for a wild swim.

Yeehaw!

Next Up: Wild Swims on the East Coast, including Thoreau’s Walden Pond (which is a lake).