The most extraordinary wild swim of my Summer ‘19 so far—and most arduous hike to it—is Jade Lake, one of the more than 700 lakes in the 415,000-acre Alpine Lakes Wilderness. I would have been happy/ecstatic if I had just loafed around on the shores of nearby Marmot Lake where my husband and I had pitched out tent, but I’m glad we heeded the advice of all the hikers we talked with on the trail: “Go to Jade,” they said. “You’ll be richly rewarded.” Indeed.

We accepted the challenge and with our day packs, lunch, and a pair of hiking poles between us, we set off for Jade Lake. It is not a hike but a steep, slow, ankle-twisting scramble across a talus slope that extends from just south of Marmot Lake all the way to a flattish stretch of boggy land on the approach to Jade. There was no trail, just a very spare but thoughtful series of cairns to guide us toward our destination. The only difference between the rocks used to build the cairns and the other rocks all around us was that the cairns were distinctively horizontal. Once we reached the first cairn, we just stood there scanning the wide slope from edge to edge looking across a field of mostly chunky squarish boulders and rocks for some anomalies: discreet piles of flat rocks—usually just four or five. Talus slopes are dynamic and it’s likely there were more and possibly taller cairns (or even trail markers once upon a time) that have succumbed to gravity, the push of rain, ice, and snow that covers these slopes most of the year.

We were in no hurry to cover the two miles. The weather was dry and sunny and the longer we baked on the hike, the more delicious the icy water would feel on our skin.

Though we had seen photographs of Jade Lake, nothing prepared us for the moment we first saw the lake. The color is laughably stunning and surreal. “Jade” doesn’t quite capture it. Turquoise? Teal? Aquamarine? Swimming-pool Blue? Maybe we should just call it “Jade-Lake Jade.”

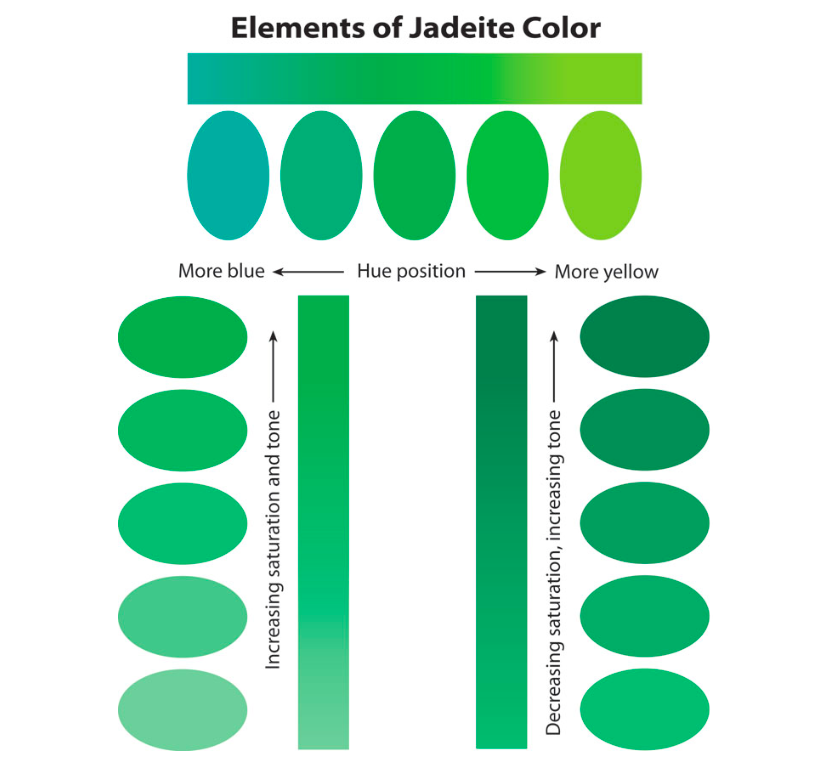

The color known as “jade” comes in many hues, tones, and saturation levels. None here or in other color charts I consulted match the water I swam in.

The color of Jade Lake is attributed to the fine, almost talcum-powder-fine crushed rock worn down by the scouring of the glaciers and carried into the lake by the meltwater. This “glacial milk” or “rock flour” as it is known remains suspended in the lake water like silt and causes the most stunning color of blue-green of the sun’s visible light spectrum to be reflected to our eyes. The other colors, the longer wavelength reds and oranges are absorbed in the lake and not reflected back to our eyes.

Other lakes in and beyond Jade Lake—and some rivers as well—show this beautiful jade color, but none is quite as thoroughly jade as Jade.

After a good long while of oohing and ahhing by the edge of the lake, it was time to swim. I dipped my feet in for a quick test of the water temperature. It was probably around 55 degrees F, maybe more. I’ve been swimming since March when an actual thermometer read 52 degrees F so I had a sense of what I could tolerate and enjoy safely. I slipped in and felt that ear-to-ear smile break across my face. I dog paddled with my head above water, spinning around so I could see the entire shoreline of the lake. I was in a vast bowl of cool liquid jade. The bottom of the lake wasn’t visible—the lake is opaquely jade but I could see my feet as if the water was crystal clear. I swam a little ways off shore, testing how far I could go toward the middle without the risk of becoming hypothermic and not having enough muscle strength to get back to shore.

One of the most challenging aspects of swimming in such beautiful water in such a remote wilderness (and working hard to get there) is knowing when enough is enough. I wanted to stay in for hours. It might be my once-in-a-lifetime visit to Jade Lake but I also didn’t want to turn myself into a shivering mass of hypothermia. I floated around a bit, then swam a few strokes, the floated some more while spinning myself around to take in the scenery. I was in a total of fifteen minutes or so, no more than 50 feet from the shore. Little did I know the best part was still to come.

Sitting quietly in the sun on the warm rocks, my husband and I heard the calls of an osprey on the far side of the lake. We eventually spotted it as it flew from the top of one tall evergreen on the far shore to another, its white wings bright against the dark green trees. Back and forth, back and forth. And then…

And then it flew over the edge of Jade Lake and the underside of those white wings and white body turned the color of the lake. A Jade Bird. It floated over the water just long enough for us to do a double-take and then fully take in this glorious natural sight. I attempted a photograph but that kind of light, that kind of ephemeral beauty, just can’t be captured.

Before you go to Jade Lake, please read the trip reports on the Washington Trails Association (WTA) page here. It looks like this lake is getting more love (and less respect) that it needs. Please tread lightly, camp quietly, swim without whoopin’ it up.

In addition to swimming in Jade Lake on this trip, we swam in Marmot Lake, Hyas Lake, Little Hyas Lake, and Lake Clarice. I had plenty of time to stare into these beautiful lakes, especially Marmot Lake where we camped. I’m eager to learn more about the different effects on our brains of the sight and sound of rippling lake water, flowing river water, and wave-rolled ocean water.