It was barely light outside at 8 o’clock this mid-January morning. I was in my bathrobe reading The Olympian, which used to take me as long to read as it took me to drink a cup of coffee. But it has sadly shriveled, like so many daily papers, and this morning it’s a three-sip paper. But I am in the mood to read. With no magazines or books within reach, I stare into the room for a while and look out the east-facing window for signs of the sun. My gaze falls on my tidy stack of Orion magazines, spines facing out, on a shelf across from me. I try to remember what I read in those beautiful, thoughtful, ad-free pages. As a nature writer, I know I found inspiration and camaraderiein every issue, but now the specifics are lost and I just have warm fuzzy feelings about this treasure chest of the finest writing about nature, culture, and place. And about the physical presence of these magazines.

Each issue is squarely and tightly bound so that each one stacks neatly on top of the other without sliding off each other and off the shelf the way issues of the New Yorker do. The issues of Orionseem to cling to each other with magnetic force, which is part of the reason they persist on my shelf—unlike the slip-sliding New Yorkers I recycle or tuck into the magazine rack at my local YMCA.

The Orions on my shelf are all that’s left from my on-again-off-again subscriptions, plus a few issues I had bought at my local food co-op when I had let my subscription lapse, minus those I had loaned or given away to friends. What was in those particular persistent issues that gave them staying power? What important and urgent ideas had I not taken to heart or acted on? Which writers and stories had I wrongly forgotten? What lovely heart-breaking stories were trapped in those pages that were now reduced to decorative dead weight on my shelf?

I walked across the room and kneeled down in front of the Orion stack. There were just fourteen issues covering a decade between 2008 and 2018. I picked up the top three from the stack and returned to the sofa and my coffee. It was time to act. Time to move ideas from the page into the world. Time to move back issues forward.

January/February 2015. Starting in the back of the issue I read reviews of four books I haven’t read. I dog-ear the page to remind myself to put Diane Ackerman’s The Human Ageon hold at my public library. I felt I have done this before. Perhaps not. Perhaps I did and let the hold expire. I hoped that when it arrives at the library I do not hear myself say, “Oh, yeah. I’ve read this.”

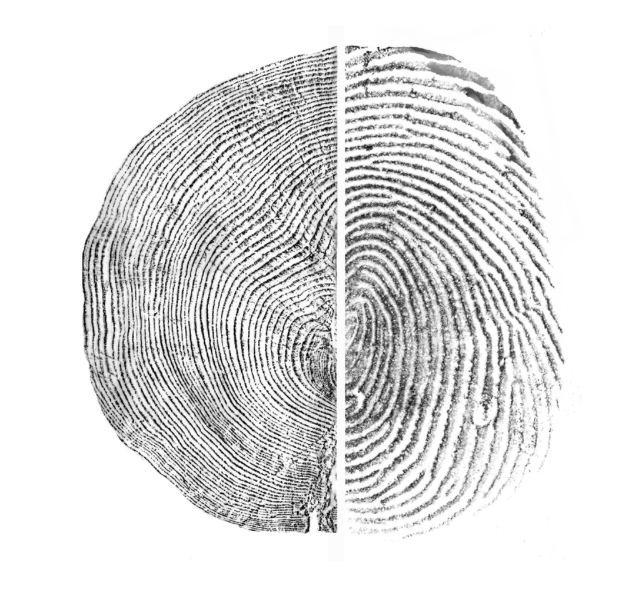

I turned to the front of the magazine and read the Preamble (the editor’s letter) and the Lay of the Land (charming short “reports from near and far.” I became transfixed by a black-and-white image of tree stump. The title is Against Forgetting. The caption tells me the artist joined two images—a wax rubbing of a tree stump and a inked human fingerprint. The wax rubbing is reduced in size and the fingerprint enlarged so the tree’s growth rings and the whorls of skin look uncannily similar. It is a breathtaking illustration. I cannot turn the page. I do not want to cover up the image with the next page. Should I order the book? Track down the artist, Nina Montenegro, and inquire about obtaining a print? How big would such a print be? How much would it cost to frame it? Where would I hang it? Once hung, would I love it for a while and then, after so many months, stop noticing it, stop seeing it, and then forget about it altogether. Is getting a framed print a meaningful response to this piece of art? Do I need to be reminded how much I love trees, intricate patterns in nature and how we are similar to trees in so many other ways? I cut the image out of the page for my friend, Anne.

Anne and I share deep druidical respect and passion for trees and forest conservation. We spend much of our time together walking in the woods, admiring trees, and appreciating everythinng they represent. Anne will love this image for the tree rings and fingerprint equally. One afternoon over tea, I presented her with the cut-out image, she had a good laugh and then recalled the details of the story about her fingerprints.

Anne was born in Canada and has lived in the U.S. for more than thirty years. In 2016, she began her application for U.S. citizenship. She passed all the requirements and tests with flying colors but she failed the fingerprint test. Her fingerprints were too faint to be positively identified as hers. She made three separate trips to the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Citizenship and Immigration Services office an hour away to have her fingerprints recorded as part of her background check. After each trip, she was told that either the inking or the electronic scanning failed to yield a set of acceptable prints. Anne was also told that our fingerprints wear off as we get older. Anne did not consider herself “old” or at least not old enough to have worn her fingerprints off. What recourse did she have? She had to make a trip to the local police station to obtain a signed document confirming she had no criminal record.

Anne became a U.S. citizen shortly afterward. What all her paperwork does not make apparent is her role as an upstanding citizen of the natural world; as an admirer and advocate of the border-crossing ecosystems, the forests, individual trees, and the birds that perch and nest in those trees wherever they are rooted; and her deep and unforgotten connection to the land and landscapes she visits. Anne is also an oral historian, a graceful and careful storyteller, and a popular columnist for the local Audubon chapter newsletter. She has a smooth writing style no whorls or spirals could possibly improve.