My friend and I had planned a swim on Saturday but it took until Tuesday to finally get in the water. The air was 42 degrees F, the water 46. This does not add up to 100, which is the number someone recommended as a guide to “swimmable” water in “tolerable” air, but we had done 88 before and so proceeded. Someone asked me recently why I swim in really cold water. I will try to explain.

There are three parts to the swim: the before, the during, and the after.

The “before” includes picking a day and time with my friend; dreading the swim (four days’ worth for this particular swim); getting into my bathing suit, fleece, wool socks, wool hat, and dry robe; dreading the swim some more; making hot tea; driving to the lake; standing at the edge of the lake waiting for my brain and body to get in sync and to decide that at this moment right now…now…now (oh, one more photo)…that at this moment now the “before” stage is over.

Self portrait of author while author’s hippie-hatted brain struggles to convince author to stay out of the 46-degree water. Shortly after photo was taken, author told brain to “get over it.” (Photo by M.M. Ruth)

Then the “during” begins with accompanying my bathing suit and wool hat into the water, slowly, up to my waist. My friend is similarly clad and nearby, but she moves more peacefully and steadily. We dip our hands in, splash water on our arms, rub our cold wet hands on our faces, look at the lake and clouds and trees. We talk to ourselves and to each other. We say things like, “Okaaaay!” “Here we go!” “We can do this!” And we do. We just drop so that the water rushes over our shoulders. I flip onto my back and kick and paddle my hands like egg-beaters and try to not scream and sing an operatic off-key note but usually fail. That I am in this very cold lake is bizarre. That I am not crying or weeping or miserable is astonishing. That I am smiling and laughing with my friend is a wild and wonderful gift.

Yes, I am very cold.

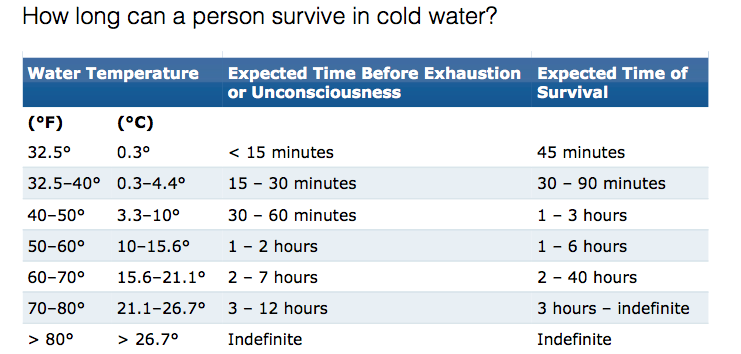

Despite my constant thrashing, my hands tingle to the point of discomfort. Is this pain? I am not sure. It’s a feeling. But it’s a sign that if I get out much further in the lake or stay in much longer, my hands—and then arms and legs—will not work well enough to get me back to shore. Keep in mind we are about 30 feet from shore but in water over our heads. We stay in maybe ten minutes then breast stroke toward shore. My friend hands me her wool hat, she dives underwater, and emerges with an even bigger smile. I am not there yet, but soon. I am still seeking and hoping to destroy my idiopathic resistance to putting my head under water.

The “after” of the swim begins when our feet touch the bottom of the lake—about ten feet from the shore—and we lunge for our dry robes, exchange wet suit for dry fleece pants and sweater, and then wrap our hands around a cup of hot tea. We talk. We warm up. We admire the colors and textures of the water, the reflections of the clouds, the harmony of water and sky and trees.

As we begin to feel a bit of post-swim euphoria (endorphins? relief? gratitude?), we slowly head to our cars where one of us will undoubtedly say, “That was perfect. We should swim again soon.” We are vague about when. Here in the “after,” I am not quite ready to start another “before”. I think of a stanza in Wallace Steven’s poem, Thirteen Ways of Looking at Blackbird:

I do not know which to prefer,

The beauty of inflections

Or the beauty of innuendoes,

The blackbird whistling

Or just after.

At the lake, we do not have to choose. We enjoy both the inflection and innuendo, the whistling and the silence, the water and the air, the during and the after.

The “after” is a really wonderful time and is in no way sponsored by dryrobe, though they do make the before and after quite pleasant, even toasty. (Photo by M.M. Ruth)