The first Marbled Murrelet nest known to science was discovered 44 years ago—on August 7, 1974—by an unsuspecting tree trimmer who had never heard of this mysterious seabird.

Hoyt Foster. Photo courtesy Susan Schwanke.

Forty-four years ago today, tree surgeon named Hoyt Foster arrived in Big Basin Redwoods State Park in the Santa Cruz Mountains of California to do a routine safety trim at a popular campground.

Hoyt Foster, age 47 at the time, didn’t know much about birds. He didn’t know that a robin-sized seabird called a Marbled Murrelet had been seen flying into the state park where he was working. He didn’t know that the location of the Murrelet’s nest was a mystery that had flummoxed birders and ornithologists for decades.

Flip-line climbing of an old-growth tree demonstrated here by Tom Hamer (Photo courtesy Hamer Environmental).

What Foster did know was how climb and trim trees—the Big Trees—the old-growth Douglas-firs and Coastal Redwoods that were over 200 feet high and several feet wide. The trees that were too big and too remote to get into by ladder, cherry picker, or hydraulic lift. The 47-year-old Foster knew how to climb such trees with little more than a pair of spurs, a climbing rope, and a flip line.

It’s no wonder the mystery of the Murrelet’s nest wasn’t solved until 1974, well after the nests of all other North American breeding birds had been discovered. Few if any birders or ornithologists were also skilled tree climbers and, even if they were, none of them had thought to look high in the trees for a murrelet nest.

Two Marbled Murrelets painted (not from life) by John James Audubon.

While Hoyt Foster was trimming trees in California’s Big Basin Redwoods State Park on August 5 and 6, plenty of people were thinking about murrelets and searching for their mysterious nest sites. The problem was that birders were looking in the wrong places. The Marbled Murrelet is an alcid, (a web-footed seabird family that includes puffins and auklets) and most birds in this family nest on the ground along the rocky cliffs and outcrops of the Pacific Coast. That is where birders, egg collectors, ornithologists had been looking for the murrelet.

The color plate (above) depicts two Marbled Murrelets by John James Audubon from 1838. The bird at left is in summer “bark-brown” breeding plumage, the bird at right in winter plumage. This is likely the only image of murrelets available at the time, but is misleading. The penguin-like murrelets are shown sitting on the ground (which they never do) at the edge of the coastal bluff (where they do not nest).

Hoyt Foster probably didn’t know about the nesting mystery of the murrelet while he was working in Big Basin Redwoods State Park. He was simply doing his job as a tree surgeon, wielding his 24-inch pruning saw in 200-foot-high redwoods and Douglas-firs to remove potentially hazardous branches overhanging the park campsites. By the end of August 6--his second full day of work--Foster had trimmed five big trees. He was relieved to have gotten this far without injury or incident.

Around 2:30 p.m. on August 7, 1974, Hoyt Foster was perched 148 feet up in a 228-foot-high Douglas-fir. He had just eaten his lunch and was about to continue his climb when he came face-to-face with a creature hunkered on the wide mossy branch. The bird was covered with beige and brown downy feathers, and was later described by Foster as “a porcupine with a beak sticking out.” When he noticed the feet of the little bird, he knew he was looking at an unusual creature. The feet were webbed, but the bird was six miles from the nearest point on the Pacific Ocean.

The bird was captured and taken to park headquarters where park naturalists identified it as the only known downy chick of the Marbled Murrelet. The mossy branch where it was sitting was its nest—not a built nest, but simply a place in the naturally occurring moss and duff.

The very downy Marbled Murrelet chick discovered on its nest in 1974 Photo courtesy Bruce Elliott (California Dept. Fish & Game)

The discovery ended the search for the nesting site of this small seabird whose secretive breeding habitats had eluded scientists for decades and brought to a conclusion the “last great ornithological mystery in North America.” This one nest proved to be the critical evidence that lead to subsequent scientific discoveries: that the Marbled Murrelet depends on old-growth coastal forests for nesting, that the logging of these forests along the Pacific Northwest coast is the primary cause the bird’s declining population, and that saving the murrelet from extinction requires protecting the murrelet’s nesting habitat.

The Marbled Murrelet is the size of a robin, its egg the size of chicken egg. (Photo by Nick Hatch, USDA Forest Service)

Thanks to years of scientific research and public support, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed the Marbled Murrelet as a threatened species in Washington, Oregon, and California under the Endangered Species Act in 1992. Despite these protections, Marbled Murrelet populations have been declining rapidly. In Washington state, the murrelet population declined a heartbreaking 44% between 2001 and 2016.

This fall, the Washington State Department of Natural Resources (DNR) plans to release a set of conservation strategies for the Marbled Murrelets nesting on our state-managed public lands. We’ll need your help during the following 60-day public comment period to ensure that Marbled Murrelets have a chance to recover and thrive in our state forests.

A coalition of Marbled Murrelet advocates—the Washington Environmental Council, Washington Forest Law Center, Olympic Forest Coalition, Conservation Northwest, Defenders of Wildlife, Seattle Audubon—will be analyzing the strategies and sharing their recommendation and information on how you can support the conservation strategy that will best help the Marbled Murrelet.

For the most up-to-date information, check here or the Murrelet Survival Project on Facebook.

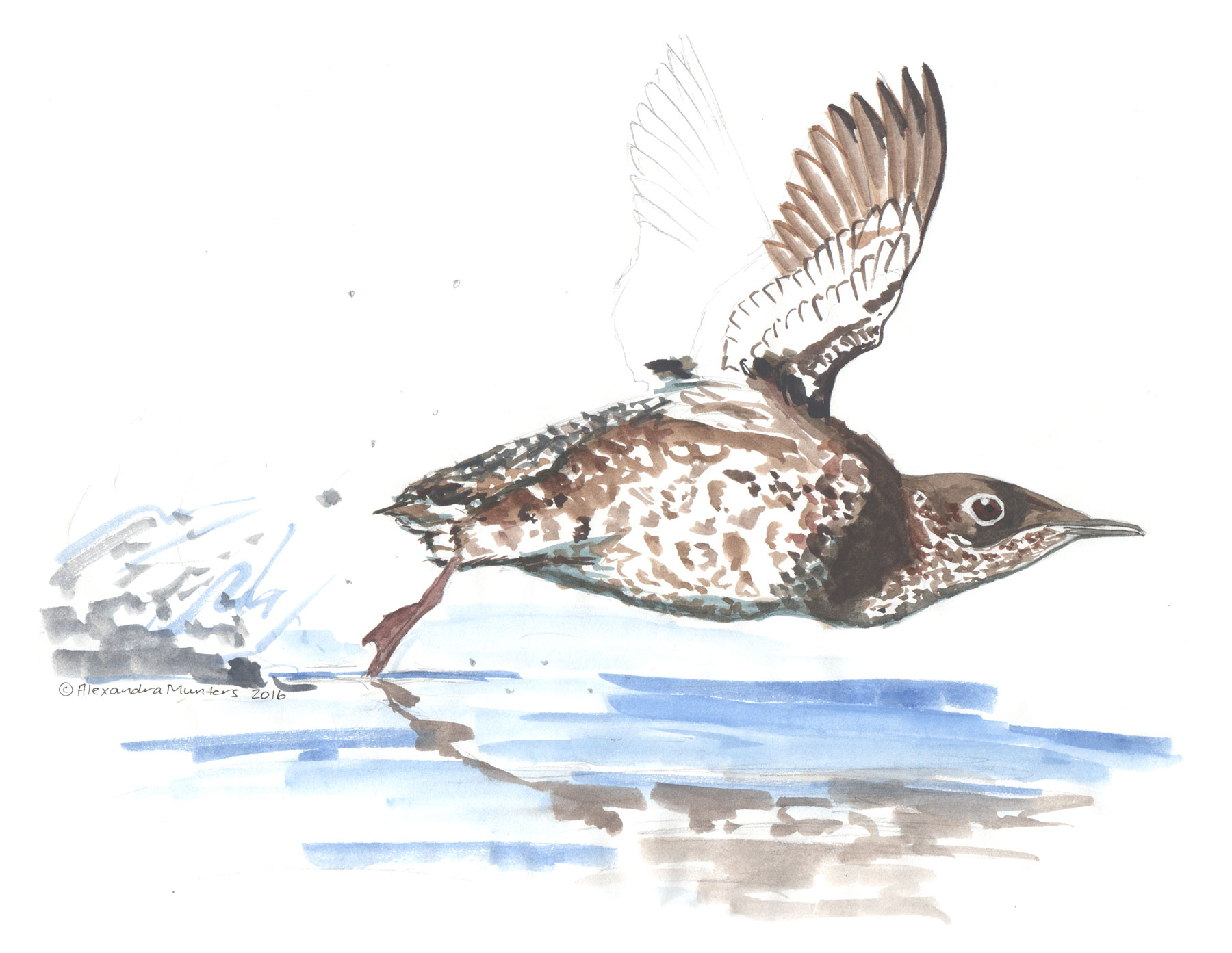

A Marbled Murrelet in breeding plumage taking off from the water. Photo courtesy Dan Cushing and S. Kim Nelson

And now a short light-hearted video to celebrate Discovery Day. Click here and enjoy!